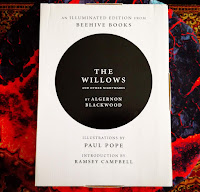

A short little look at the contents of Beehive Books' The Willows.

First off, the Introduction by Ramsey Campbell is an odd one, as there are definitely insights to be found here, but nonetheless, there seems to be something a little off. There are words out of place, misused (or at the very least, they seem to be misused, though I might just be stupid.), there are also a few missing letters, and most annoyingly, some of what Campbell has written seems to be a bit out of sync with what the stories are actually about, as if he wrote an introduction to something he barely remembered rather than something he had read recently.

-----

The Titular

The Willows is the first and longest story in this collection, and takes up, together with its own many double-page artwork pieces, around half of the book. The choice to lavish this much time and effort on it is quite understandable, given that the story itself is legendary in some circles, frequently dubbed one of the best tension-building horror stories of all time, effortlessly evoking awe rather than horror, something that is very hard to do.

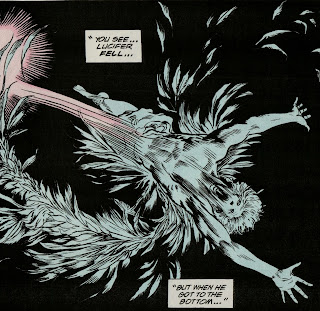

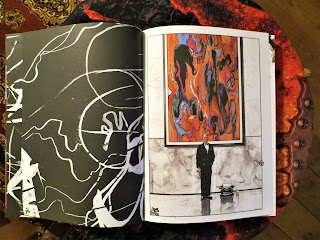

The art is moody and striking, and manages to gift the text and the imagery it conjures up, already pretty strange, with an added layer of strangeness, an alien colouring to all its elements. The art didn't really always follow what was described though, and the 'scribbles in the air' were definitely a loose and rather more ethereal depiction of the strange phenomenon the narrator is presented with as he stares out of his tent in the night.

However, the story itself is pretty good. We follow the narrator and his companion on their canoe-journey down the Danube as they arrive at a place where the mighty river pools into a vast marshland, isolated and dotted with islands overgrown with willow-bushes. Struggling with the river and irritated by the ever-present roaring wind, they decide to make landfall on one of the islands to set up camp.

Shortly after they begin to experience various strange phenomena and a building sense of unease. Try as they might, they aren't able to dispel their misgivings and soon after they come face to face with an undeniable supernatural presence.

The story does indeed manage to slowly ratchet up the tension to a level where the reader is compelled to venture further. It never ends up getting really scary, but I've never found this to be the case in most horror literature anyway. But I did really appreciate that some events that at first were thought to be commonplace later were revealed to be quite ominous portents of the things to come. It gave quite a thrill, and even though it's a writer's trick it's pretty effective when delivered with skill.

The conclusion is undeniably a deus ex machina though, and there is absolutely no information concerning the exact element that manages to divert the what seemed to be up until that moment an unavoidable doom for the two travelers.

-----

The second story,

Accessory Before the Fact, is a bit of a lesser tale, a lot shorter and trying for the same vibe of a supernatural experience in a lonely, isolated area, as a man on walking holiday is overcome by a strange and subtle compulsion to take a different road than the one he had planned on. On the unfamiliar road, he meets 2 vagrants who seem to harbour ill intentions towards him. As they attack him, he passes out and then wakes up out of a trance at the very crossroads that had sent him awry earlier.

Overcome by terror he hurries along to his destination, but he's plagued by doubt and yet also overcome by the certainty that what he had just experienced had not been meant for him.

Though its goal is very similar to that of the Willows it maybe pulls it off a little better, but only by the grace of never even giving a hint of what this supernatural agency might be, which is something where the Willows might have overplayed its hand a little. Also, the title of the story is a bit of a misnomer as it seems to be exactly the point of the story that the protagonist wasn't even supposed to know of the thing that is to come, let alone act to stop it from happening. As such, just dubbing this tale 'The Glimpse' or 'The Message' would have been way more apposite.

-----

Thirdly,

Smith: An Episode in a Boarding House is good little tale, catering quite nicely to my specific tastes.

A professor tells a tale of a supernatural experience from the time of his student years. As the audience sits with baited breath, he tells them of the man Smith, a charismatic and intense fellow, who inhabited a different room in the same boarding house where he had his residence, and whose mysterious activities led him to experience a glimpse of the truly awesome heights attainable by those deeply interested in the occult.

It's a fun little tale, but I find I don't have much to say here. Smith is an interesting and intense character, his physical description evoking a sense of the alien with his seemingly mismatched body parts, and his manner effortlessly evoking attention and interest. Oddly, in these 5 tales, only 2 characters are given an in-depth description;

Boarding House's Smith and the Swede in

the Willows. Both characters are almost eerie in their interactions with their surroundings and seem more removed from the world than the narrators they live alongside with, as if they are more vulnerable to whatever is about to encroach on the borders of their reality.

The theme of awe in the presence of the supernatural and the unexplainable rears its head once more, and by now I've come to realize that this, in Blackwood's tales, feels different than the supernatural in other fiction, less overtly malign maybe, or maybe just inimical because it operates in different realms than us, (living) according to different rules.

-----

An Egyptian Hornet

An Egyptian Hornet then is a bit of a surprise as it's not at all what I expected. I was expecting maybe something along the lines of Marsh's

The Beetle except immensely shorter, but instead what I ended up getting was a comedic little tale of man's pettiness, which also at the same time manages to give one an insight into the theory of relativity; one man's mere-bug-to-be-swatted might as well seem like a dangerous monster to another.

It's a bit of a throw-away story maybe, but it shows that Blackwood had more up his sleeve than horror stories. There are also enough elements here to, if one is so inclined to do a Freudian reading of the the story.

-----

The tale that closes out this collection has a theme that'll be familiar to any avid horror reader. Led by dreams of prophecy, a scientist goes on a quest to find a forbidden tome of secret knowledge. He leaves a hopeful optimist, and comes back a changed man. Though successful in his quest he seems to have found more than he expected, and gripped by the revelations of The Tablet of the Gods, the once-great man begins to spiral into a deep depression.

His assistant, unable to do anything but watch his friend's decline, is forbidden from reading the tablet until the man's death. But with the scientist's rapidly declining health, the time of revelations draws swiftly closer.

The Man Who Found Out (A Nightmare) is probably my favourite story in here, with elements of nihilism, occultism and even a few mentions of 'Gods', though this is probably more of a metaphor, rather than any real indication of divine mythology.

The story's resolution hints at truly terrible revelations, though of course, we aren't privy to them, and we are left outside, wondering if any text, book or tome, could ever engender from us a reaction such as that of the narrator. Probably not, but one can hope.

-----

The artist's note is worth a look and quite insightful in some places, though it stopped short of being able to explain to me why, in certain pieces of art, the imagery didn't correspond with the text at all, e.g.; a naked man depicted where there seems to be no naked man in the text, or, violently iridescent sky-scribbles where the text seems to point to a more bronzed palette, and limbs of flowing darkness, etc...

Minor quibbles aside, Paul Pope's piece really does manage to give some rather interesting background on Algernon Blackwood and specifically on how The Willows short story came about.

On top of that it gives some insight on the collaboration between the artist and the producers of the book. It seems to reveal that the artist had a lot of say on what'll be put in the book, etc, down to the choosing of which stories to put in. It's something that caught my attention, is why I mention it.

Anyway, Beehive Books' edition of The Willows is lovely, and the short stories therein also turned out to be rather good. A great addition to the shelves.